In an era of (desired) minimalism and the attraction of Marie Kondo, living life with less stuff has been suggested as a route to greater happiness.

In an era of (desired) minimalism and the attraction of Marie Kondo, living life with less stuff has been suggested as a route to greater happiness.

Most of us appreciate a goal to reduce clutter in our homes and offices. There is a difference between having too much stuff and being a hoarder, mainly in terms of the types of items collected and not thrown away, as well the emotional ties that people have to various objects.

In this world of face paced consumerism people can buy much more stuff than they could in the past. Many people in the first world may feel burdened by the amount of possessions they have. You may be experiencing the overwhelming phenomena of stuffocation: the experience of stress caused by owning so many items that you don’t know how to use, store, or manage.

You might be suffering from stuffocation if you:

1.Regularly misplace items in your home or office

2.You buy items to replace items that you have misplaced or lost in your home

3.Rather than feel joy when you look at all of your possessions, you feel overwhelmed or a sense of dread.

4.You have difficulty moving around rooms in your home because of too much stuff.

5.Your cupboard, draws and cabinets are full to the brim

6. You find it hard to discard of items you now longer regularly use

7. You have to have an external storage unit

8. You’ve read more than 2 books on decluttering and this has not made a significant difference to your decluttering practices

9. You feel embarrassed when people come into your home because of the amount of disorganised stuff.

At this point I need to make a confession – I have experienced 9 out of 9 of those listed above. I once brought a de-cluttering book to replace the de-cluttering book I had lost in my home. This blog is by me, and for me at the same time.

Part of the reason I believe we struggle to clear clutter is that we tend to address clutter from a practical approach rather than a psychological approach. De-cluttering books provide advice how to sort items and where to recycle items. Whilst this is very helpful, it can leave the feelings we have about things unaddressed.

Its worthwhile to take a moment to explore some of the psychology of stuff, the thoughts we may have and how to overcome this thinking. Essentially we need to understand that objects are NOT just objects, we need to understand our own personal meaning of ‘things’.

Fear of running out or not having enough. If you feel you keep things, anything, cups, dresses, shoes because you may need them if you give them up, or at some point in the future may not have enough of this item ask yourself the following series of questions as a reflection.

Reflection: Did I once have “not enough” and was anxious or fearful of that time? Did I cope with my lack of things then? Can I gain faith that I might be able to get past that moment again? Reflect on these questions. Is it unlikely that you will suddenly become poor in the future and not have enough of the things you are keeping now? What could you do to ensure that you have enough finances to secure your future? Could you train in some small part time job that would give you enough money to buy a new cup, dress, book? The likelihood is yes.

Action: Count how many you have of certain items. Then decide what is a reasonable amount for you to have of that item, in reality. How many pairs of shoes do you really want to have displayed? How many books? Once you have set a cap of how many, start to sort out these items into those you love, versus those you like, and those that have no meaning at all. The last pile is the first for you to discard.

Saving for the future use. Items that you are keeping for a future rainy day need to be considered in a slightly different way. If you’ve changed jobs from a corporate job to one where casual attire is acceptable you may have a wardrobe full of clothes that occupy space, but are not longer in use. Some questions that may help with your thoughts and feelings around these items might include

Reflection: Do I love these items, or am I scared to get rid of them? Could someone else benefit from these items – a person at the beginning of their career? Will I, change my lifestyle again and go back to that lifestyle if I have a choice? If not, can I let ½ of these items go? Can I give myself one small storage box, a draw, something little that I can keep some of these items – just in case, but not the amount of space they have now?

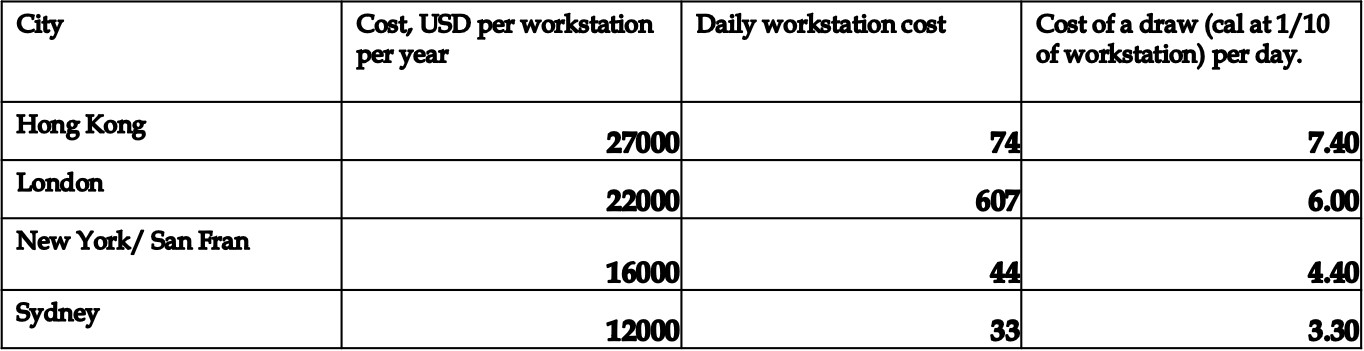

Action: Count up how many of these items fit under this criterion. How much space in your home is dedicated to storing this space? Can you put a value to the cost of the storage space used to save these items. For example, you can use the following comparative assessment of space value provided by Cushman and Wakefield’s annual assessment of costs of offices around the world, we can make a brief calculation of the cost to store such items.

For example, in Hong Kong, the cost of a draw could be calculated to be USD 7.40 per day, that’s USD 2700 a year. Once you put a monetary value to storage, you can potentially force a relative value assessment. If it costs you (virtually) this much to save these clothes (or other items) does this change your perception of their value. Decide on a small storage you are willing to dedicate to maintain these items and prioritise what you love, what you like, from what simply fills space. Recycle those clothes or items that are not your favourites.

Feeling out of control, and not willing to let others help. Do you feel embarrassed about your space? Have others offered to help you, but you reject their offers due to embarrassment? You can use this embarrassment to your advantage. If you feel out of control or ashamed about your stuff these reflections may help.

Reflection: What is the shame of having too much stuff? What do you think it says about you? What do you worry that other people might think of you? Is this true? How do you determine your value in life, how could your space reflect those values? Does having too much stuff fit with your perception and values that you hold for yourself? How can you work towards accepting yourself, with too much stuff, as well as without too much stuff?

Action: Use your embarrassment as a motivator. Tell your friends that you are working on eliminating clutter and would like their support. Define the support you might like. Perhaps you’d rather discuss what you can do with items rather than have physical support. Perhaps you can agree to invite friends over for an “after the clutter” celebration once you have some spaces sorted. Friends who use your clutter and stuffocation to judge you, may need to be told that their assessment of you hurts your feelings and makes it harder for you to start the process, even though you acknowledge that they want to help. Set yourself your deadline. Get going.

The joy of shopping and collecting – Sometimes we gain too much stuff because we like the process of acquisition too much. Is it possible you are addicted to buying more things, even when you don’t need them? If so, you might benefit from reading our blog on FOMO as this might be part of the issue. [Whilst there may be pleasure in shopping, and it may not greatly impact your financial situation, acquiring stuff as an activity is worth thinking about. https://reddoorhongkong.wordpress.com/2017/04/25/fomo-read-this-now/

Reflections: What is it about shopping or acquiring items that brings you joy? Is there any other elements in your life, such as creativity or health, that could replace this activity in a more constructive manner? Do you shop to “keep up appearances”, and if so, what does it mean if you cannot achieve this goal? Are you worth less as a person?

Action: Each time you want to buy a new item consider the following:

First of all, walk away, do not buy it immediately. Only those items that you continue to remember then become truly considered.

Before you do buy it, shop in your own cupboards to see if you have a similar item already. We often buy items that are remarkably similar to those we have already. Is this really significantly different? Would you consider to move one item OUT of your home in order to move this item IN? As with the processes above conduct some form of opportunity cost analysis before you buy. Is this the best way for me to utilise HKD500?

Ask yourself: Would I get more joy taking a friend out to lunch, or taking a cooking class with a friend instead? When we look at deathbed regrets, it never seems to be mentioned that people need to buy more. What they regret is spending time with people, having experiences, and pursuing their goals.

Holding onto precious memories – sometimes we have items from the past, items that remind us of special occasions or people, and we hold onto them. This might include old clothes, books, photos, artwork, and even old tools or jewellery. Compiling precious memories may lead to accidental clutter. Some reflective work that may help.

Reflections: are you keeping items as a way to show people that they are important, or were important? If you lose these items, will those loved ones be less important? In what other ways, besides holding onto items, could you celebrate items from ancestors or loved ones. Perhaps you want to keep special photos of your children, or their artwork. Do you need to keep all of these items to demonstrate your support and love? What other actions could you undertake to show your love for the child featured.

Actions: Consider ways to store precious items in alternative storage format. For example, take photographs of children’s artworks and building a virtual album. For items from ancestors consider selecting your favourite items and framing them so that they are displayed beautifully. Then you can potentially pass the other items from the collection away. Old jewellery could be redesigned. Old clothes could be made into sentimental pillows.

I hope these reflections and activities help. I intend to give them all a chance and I hope you will too. Try to build a habit to be more mindful of they items you already have, their purpose, and their meaning. Embrace change from a positive angle. Praise yourself for letting go. There is no shame in moving forward and learning to live with less.

#stuffocation #worldrecyclingday #recycling #declutter #mentalhealthessentials #reddoor

#mentalhealth #hoarding #minimalism #mariekondo