Music has been frequently used as a therapeutic medium for students with special educational needs (SEN). Potential benefits extend beyond improvements in musical performance (1).

It has been suggested that even children who are non-verbal as will develop better communication, expressive and interaction skills through the use of music as a therapeutic medium. (1).

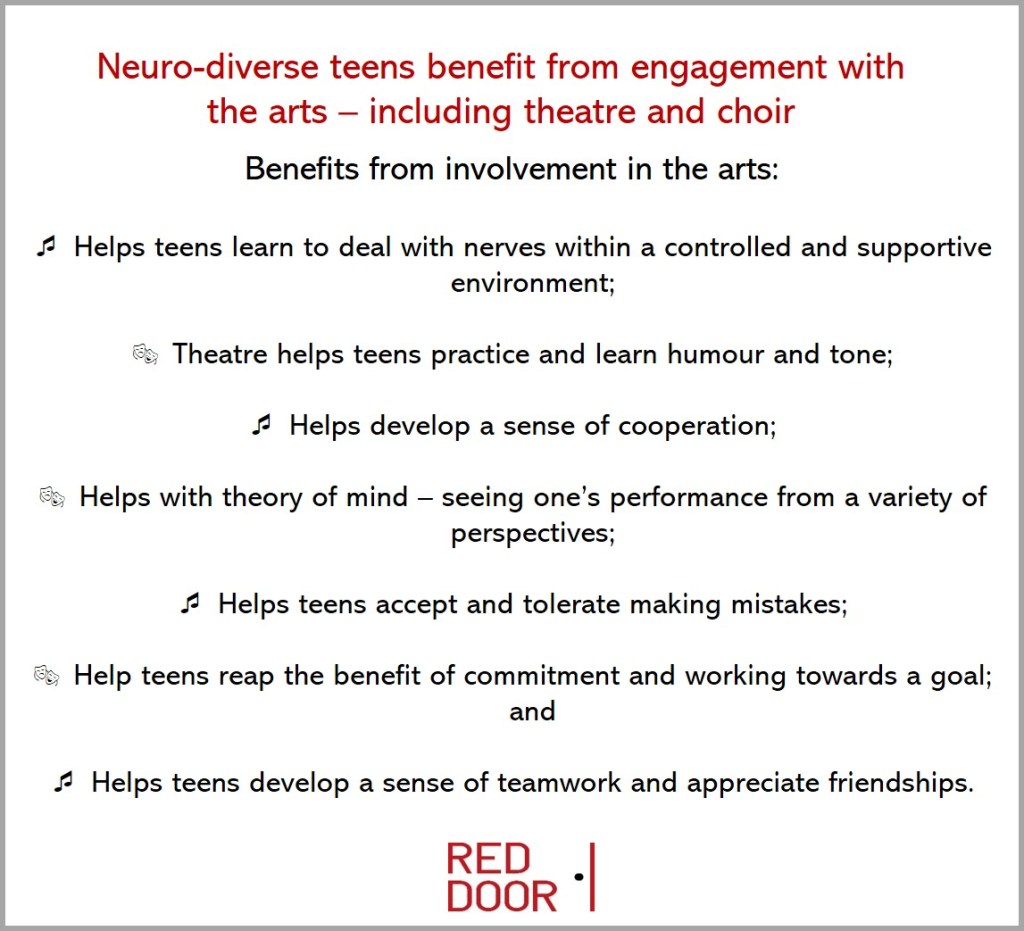

I recommend that any parent of a child experiencing developmental delays consider therapy with music. In fact I believe all arts are of benefit to all children, and especially those with special educational needs (5). Academic research is generally positive as to the benefits, and of course, if it is not you can always quit.

The subject of less research is the use of music as part of the second wave of intervention, with teens and older kids (4). Personally I believe the window for growth opened during the key second wave may benefit from exposure to music and music therapy. In fact many musical skills only emerge in middle to late childhood (6), and therefore music training in these years may reveal previously unrecognised skills. It was during those years that our differently wired child became aware of music, and began to flourish in response.

One particular arena of music therapy that has seen positive improvement for children is the arena of singing (4). Differently able teens are able to focus in a manner that they don’t in other classes. Singing involves many skills including the production of sound, pitch matching, volume control, breathing, posture, and working collaboratively with others.

Singing is seen as a potential equaliser for differently abled teens . These teens can often sing as well as mainstream children, , leading to opportunities for those teen# `to be better accepted (2, 7).

Uodate on Voc-abilities – A melodious experiment.

Uodate on Voc-abilities – A melodious experiment.

Against the backdrop of the potential benefits of music therapy and the perpetual need to enhance artistic and cultural opportunities for people with disabilities in Hong Kong we decided to set up a choir in 2018. Choir practice is not only a social activity, it appears to offer numerous social and educational opportunities for mainstream members (8). The choir is open to teens and adults with Special Educational Needs who can sing in English. Whilst this does limit some local access we now have 15 members – aged from 13 to 25 who encounter a range of challenges in their lives including chronic anxiety, autism spectrum disorder, blindness, and developmental delay.

During the pandemic the choir experienced a variety of challenges. We could not meet in person, the original choir coach left Hong Kong, and shows have not been possible. As an result we haven’t recruited new members during this time since choir rehersals and practices have been on and off. Our established members stuck with the programme, but even so we lost a few members. Recently we held our first concert in over a year.

I’ve observed so many benefits of choir for our members. Choir members comment that they feel like a team, and have a sense of belonging once they joined the choir. For a few of the members parents mentioned that this is the first environment that their child was happy to be associated with other SEN teens. Feedback after the first year of choir indicated improvements in memory, communication, expressiveness and socialization.

We’ve seen children blossom in confidence and capability Teens which were complete choir novices in September 2018, are now confident performers often called upon by the choir director to deliver solo components of songs.

Choir is a challenging environment for some members. Some of our members have sensory challenges and find the volume of choir very uncomfortable. At the same time they clearly crave to be with their choir members and choose to stay in the room rather than leave. It seems the desire to be part of the group is more compelling than their desire to withdraw, which they would typically perform. They even learn to withdraw their fingers from their ears, eventually, so that they can match the volume of the group.

A couple of our members have also joined mainstream choirs in addition to Voc-abilities. even when they have had to audition and no accommodation for their special needs may be provided. Hence this choir is also providing more opportunity to mainstream teens to experience that non-typical kids are as capable of they are, and can be as obsessed with show tunes as they may be. Barriers are hopefully being broken down.

If you would like to see Voc-abilities in action please visit our YouTube video, like us on Facebook and let Angela know if you’d like to see them in action.

Ingredients of success – I’d encourage others to set up similar choirs in their cities. Here are some of the components that I believe make Voc-abilities a success.

Broad repertoire – Our choir focuses on show tunes and popular songs. Music therapy advice unusually suggest that you start with what kids love. We threw our kids in at the deep end and it actually worked. We do not sing an babyish songs. One third of the songs are unknown to the choir before we sing them. This way we give some comfort with some familiar tunes, but our teens have come to expect that they are going to learn something new. This process also “normalizes” typical anxiety around learning a new song. This is explored, respected and discussed. And then we learn the song. The repertoire is constantly expanding and is stretched by the addition of progressively more complicated songs, word play, and harmonies.

Great choir director and teacher. The teacher needs to understand the technicalities of sound, break songs down into suitable components, and build the performance of harmonies using scaffolding. Of course a positive attitude is a must.

Emotional and behavioural support. Help on the ‘çhoir’ floor to keep members stay-on-task, work to modify non-focused behaviours, talk with anxious members, as well as help members sing. We have teachers on hand to do this. Overtime some choir members have act as student leaders and offer to regulate other members expectations.

Building sense of belonging to a group. We work to build a sense of being a group member. We have a WhatsApp group on which we share relevant information about choir, but also information about members including their birthdays, reasons they miss a session, and other personal information. The members feel connected inside and outside choir. The parents are also connected. Not only does this keep them informed, and able to support.

Opportunities to perform. Whilst I would advise you to limit performance opportunities to less than 4 in a year, performances provide a crescendo moment for a choir. It is cathartic to work towards, and achieve, a goal. Anxiety is part of this process and we work with those individuals accordingly.

Expectation of supportive environment. Members are encouraged to audition for solo components of songs. When they audition they receive praise and encouraging applause form other choir members. We do not permit laughing at our friends. Kindness is king.

Transparent process to rewards. Solos are only allocated by the choir director. Members are expected to practice and perform their solos and only then can the choir director decide who will earn a solo spot.

Great members. Our choir members work hard, and its clear in their progress and performances.

If you would like to learn more about Voc-abilities contact manager and founder Angela at angela@reddoor.hk or check us out on YouTube.

References

- Allyson Patterson (2003). Music teachers and music therapists: Helping children together.

- Marina Wong and Maria Chik (2016) Teaching students with special educational needs in inclusive music classrooms: Experience of music teachers in Hong Kong primary schools. Music Education Research.

- K Scior, Y-K Kan, A McLoughlin, and J. Sheridan (2010). Public attitudes toward people with intellectual disabilities: A cross-cultural study. Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities

- Marina WY Wong, BW Leung and CO Tam (2018). Music learning outcomes and music teachers’ expectations. Trialling an adapted music curriculum for students aged 15-18 with intellectual disabilities in Hong Kong. Asia-Pacific Journal for Arts Education.

- Martin Comte (2009). Don’t leave your dreams in a closet: Sing them, paint them, dance them, act them… Australian Journal of Music Education.

- B Ilian, P Keller, H Damasio, and A Habibi (2016). The development of musical skills of underprivileged children over the course of one year. Frontiers in Psychology.

- K McFerran, G Thompson, and L Bolger (2015). The impact of fostering relationships through music within a special school classroom for students with autism spectrum disorder: An action research study. Education Action Research.

- Hilary Moss, Jessica O’Donaghue, and Julie Lynch (2017) Sing yourself better: the health and well being benefits of singing in a choir. Irish World Academy of Music and Dance.