Executive functioning skills—such as planning, organizing, prioritizing, self-checking, and shifting—are essential not only for academic achievement but also for a child’s holistic development and self-esteem. These skills play a vital role in enabling children to navigate various life domains, from academic settings to social interactions. Recognizing individual strengths and weaknesses in this area can empower students to take charge of their educational journeys and personal growth.

What Are Executive Functioning Skills?

Broadly defined, executive functioning encompasses a range of cognitive processes that support learning and personal development. Strong executive functioning enables children to:

- Organize Materials and Time: Efficiently manage tasks and responsibilities.

- Employ Memory Strategies: Utilize techniques to enhance information retention.

- Maintain Focus: Concentrate on tasks and minimize distractions.

- Enhance Self-Awareness: Recognize their organizational strengths and weaknesses and respond accordingly.

The Impact of Weak Executive Functioning

Children who struggle with executive functioning often encounter significant challenges that extend beyond academics, including:

- Inefficient Work Habits: Difficulty completing tasks effectively, leading to frustration.

- Underperformance: Challenges in demonstrating true abilities in exams and assessments, which can negatively impact confidence.

- Forgetfulness: Regularly forgetting essential materials or equipment for school, resulting in feelings of inadequacy.

- Difficulty Distinguishing Key Information: Challenges in identifying important details versus errors.

- Poor Self-Concept and Low Self-Esteem: When children find organization difficult, they may engage in negative self-talk and develop a negative self-image.

These issues can escalate as children transition from primary to middle and high school, and beyond. Without targeted support, the implications of weak executive functioning can persist into adulthood, affecting personal relationships and professional success.

The Importance of Assessment

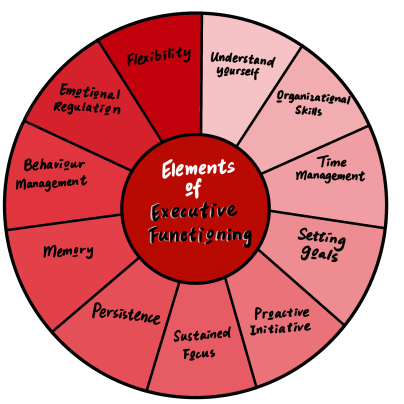

A comprehensive assessment of executive functioning skills can provide valuable insights into a child’s cognitive processes, highlighting areas of planning and performance that require additional support. Assessment tools typically involve rating scales that can be completed by the student (if they possess sufficient self-awareness) and close adults. These assessment questions focus on components of executive functioning that may need attention. At Red Door, our proprietary executive functioning assessment explores various domains, including self-awareness, organizational skills, goal setting, flexibility, emotional regulation, meeting behavioural expectations, proactive initiation, sustained focus, memory, and persistence.

The Broader Impact

Enhancing executive functioning skills can lead to a more organized, confident, and resilient child. As students learn to manage their time and responsibilities more effectively, they not only improve academically but also bolster their self-esteem and overall well-being.

Understanding and addressing executive functioning is a crucial step in nurturing well-rounded individuals who are prepared to tackle the challenges of both their academic and personal lives.

Key domains within executive functioning.

Understanding Yourself / Self-awareness as an Area of Executive Functioning

Self-awareness is a critical component of executive functioning. Some individuals may overestimate their abilities in certain tasks and fail to perceive themselves as others do. For instance, they might believe they are more cooperative or attentive than they actually are. However, when parents or guardians assess their child’s performance in these areas, they may offer a significantly different perspective.

It is essential to recognize both strengths and weaknesses while maintaining a hopeful yet realistic approach to the challenges we encounter. You may not yet be proficient at a task, but avoiding remedial education or support can hinder your ability to improve; growth often requires engagement with the right resources.

Children sometimes define themselves solely by their weaknesses, so it is important to challenge this mindset and encourage a more balanced self-view. Self-awareness also involves recognizing the level of effort you invest in your projects. Ask yourself whether you are striving to do your best or merely getting by, and consider if you are conscious of the decisions you make regarding your strengths and challenges. Some may find it difficult to identify these aspects on their own. Typically, we guide children and teenagers to seek objective and constructive feedback to enhance their self-understanding, particularly if self-awareness is an area of weakness in their executive functioning. This feedback can provide valuable insights, helping them to recognize their abilities and areas for improvement more clearly. By fostering self-awareness, we empower individuals to navigate their personal and academic challenges with greater confidence and resilience.

Organisational skills.

Organisational skills are a crucial component of executive functioning. Being organised involves having a designated place for everything and ensuring that all items are in their proper locations. It also includes establishing a system—such as a method or routine—that helps your child or teen manage the items they need on a daily basis for specific classes while remaining aware of these systems.

Often, children tend to carry too many objects and need to learn how to streamline their belongings, ensuring they only take what is necessary. If your child frequently arrives at class with the wrong equipment, they may require support to enhance their organizational skills. For children who struggle in this area, we typically assist them in developing customized checklists and planning schedules. These tools help them know what to do and include training on how to review and organize their schoolbags effectively.

Flexibility.

Changes can occur in schedules, task parameters, and even your child’s ability to attend school or participate in after-school activities. How does your child respond to changes? Are they flexible, emotional, or rigid? Beyond maintaining schedules, it is important to develop flexibility in life—especially when situations do not unfold as we expect or feel comfortable with. For example, as the school year progresses, children may suddenly find a subject difficult that they previously found easy or required little effort.

I have observed that some neurodiverse children can read easily from a young age due to their extensive memory skills. However, around the age of 8 or 9, we may realise that they are unable to read phonetically and need to revert to basic reading skills. These setbacks are often short-lived but can be frustrating for individuals who were accustomed to reading with ease, only to discover that the material has become significantly more complicated.

Being flexible helps individuals cope with these situations effectively. Learning to manage shortcomings or mistakes can be challenging even for adults, but developing this skill is crucial for resilience and adaptation.

Emotional regulation.

Being able to understand and manage emotions is an important skill for children and teens. Sometimes, children struggle with anxiety, frustration, boredom, or anger, and these overwhelming feelings can interfere with their academic performance. For example, when a child experiences strong feelings of anxiety, they may perform poorly on formal assessments. Additionally, children may express intense emotions in ways that damage their relationships with friends or family. As social connections are vital, when a child’s emotions negatively impact their relationships, it can also affect their academic success.

Helping children develop emotional literacy skills—such as monitoring their reactions and recognising the thoughts they have during emotionally charged situations—can support the development of more regulated responses. Often, sessions with a counsellor or psychologist, as an objective observer, can be a valuable step for a child or teen to begin understanding their emotional world and their reactions to it.

Behavioural expectations.

Learning to behave constructively in specific situations is essential for successful studying, school attendance, and future employment. Knowing how to behave appropriately helps children become popular and remain connected to their community. Children who are unaware of social rules can be excluded, sometimes without understanding why.

Behaviour management is closely tied to emotional regulation. Children may feel angry, but if they start hitting or damaging property as a result, they are breaking social rules about how one is entitled to behave when upset. If your child frequently gets into trouble at school for not staying on task, and other children are instructing them on how to behave, both teachers and peers may become frustrated. Your child might explain the situation as “others are too boring and want to be nerds,” but from a psychological perspective, we consider four components:

Do they know the rules exist? (Are they unaware of social cues around behaviour?)

Do they knowingly want to break the rules? (Is there some oppositional behaviour present?)

Can they choose to follow the rules if they want to? (Are there other factors involved, such as sensory processing challenges?)

Are they avoiding the task altogether? (Is this a way to escape work they lack confidence in completing successfully?)

If we encounter a child who struggles to understand behavioural expectations, we will likely spend time investigating to uncover the underlying motivations, misinterpretation of cues, and possible adaptive avoidance strategies the child may be displaying.

Proactive initiative.

The ability to start a project without repeated prompting is an important skill for achieving academic success. Proactively managing a task is not just about beginning it; it also involves remembering that the task needs to be completed and taking an appropriate approach—such as breaking it down into steps, especially if the task is complex or involves multiple stages.

For example, producing a book report requires reading the book, making notes about the story and characters, drafting the report, and then finishing it. These steps can be divided into different tasks or days so that the project does not become too overwhelming.

Some children find starting a project—or figuring out how to begin—overwhelming. As a result, they may procrastinate and seemingly avoid the activity entirely. By helping children break a project into its component parts, we can support them in working through each step. They may not fully understand the parameters of the task, and assisting them in clarifying these components is especially beneficial for producing quality work at each stage of the process.

Sustained focus.

Having sustained focus across a task is important. Some children excel at starting a project, but their efforts tend to diminish as they encounter the more tedious or complex parts of an assignment. Maintaining focus and effort when tasks become lengthy or uninteresting is challenging, yet it is a key factor in long-term academic success. Consistency is essential for sustained progress.

For some children with attention difficulties, the middle phase of a project may require additional support to maintain engagement. If we encounter a child struggling to sustain focus, we may help them understand reinforcement schedules and teach them how to break a task into smaller, manageable parts. When dividing an assignment into smaller components, we work with the child’s developing attention span, allowing them to alternate periods of study, rest, and activity. Timers can assist in establishing realistic and achievable schedules.

In exploring reinforcement schedules, we might set up external rewards to help the child develop better attention spans during study time. For example, they could work for a set number of minutes, after which they earn a preferred activity, such as watching a favourite television programme or using the iPad. It is important to ensure that the reward scenario is appropriately balanced to motivate the child and ensure the work is completed.

Ideally, a child finds the “satisfaction of good work” to be its own reward. Sometimes, we need to help children recognise the value of a job well done and how it contributes positively to their self-esteem. We should aim to foster a healthy relationship between effort and outcome, encouraging a positive self-perception and avoiding the use of shame or blame as motivators.

Persistence or Stick-to-it-ness

This refers to the attitude of “sticking at something” without losing motivation, becoming overwhelmed, or giving up when the task becomes difficult. Children and teenagers can sometimes give up too easily, so we work with them to develop strategies that help them persevere when the going gets tough.

In addition to the act of quitting, children can become discouraged by their own perceptions of themselves. We aim to encourage children to remain persistent in the face of challenges, fostering an understanding that challenges are a part of life and that we can meet them with resilience. When they do, it boosts their self-esteem; however, this is often easier said than done.

Breaking persistence down into its components, we might examine what motivates the child, their beliefs about themselves, whether they possess problem-solving skills that can be applied to new situations, their self-awareness regarding the task, and their ability to self-soothe when situations become difficult. Typically, a personalised approach is developed for each individual to help overcome their specific obstacles to persistence.

Memory skills.

Working memory, in particular, supports children’s success at school. It is the dynamic system that helps them understand the requirements of a task while simultaneously holding and manipulating relevant information stored in long-term memory to complete that task.

Children may struggle to remember facts, processes, or formulas and may require training to improve their ability to retrieve information effectively. In some cases, more complex memory issues can lead to filing errors when attempting to organise and store information. Many memory difficulties can be addressed through targeted training.

When exploring memory challenges, we first focus on understanding how information is processed into memory, identifying which types of input are more difficult to remember. Once we have a clearer picture of these input challenges, we work on developing strategies to manipulate and access stored information more efficiently.

Sometimes, we utilise online tools or games designed to enhance working memory. Children with memory difficulties often experience feelings of low self-esteem attached to their challenges. They may compare themselves unfavourably to others, which can affect their confidence. It is important to support and boost their self-esteem as part of the process of improving their memory skills.

Goal Setting

Understanding the goal of a task, as well as overall goals at school and in life, helps children and teenagers focus their attention on activities that will be most beneficial to them. Learning isn’t just about normalising everyone or bringing them up to a passing standard; sometimes it involves recognising areas in which they excel and finding ways to stretch those strengths beyond what they thought possible.

Goal setting supports children and teenagers in reviewing their work, managing their time effectively, selecting appropriate mentors, and imagining what their lives could look like. If a child or teenager faces challenges in this area, we help them understand the purpose of goals and dreams, explore what is needed to pursue these aspirations, and learn how to work towards them with sustained effort.

Ideally, a child’s goals should be based on their individual strengths and interests, rather than solely on their parents’ or friends’ expectations. They might even consider creating their own personal board of directors to help them start achieving their dreams.